PART TWO: THE REST OF THE STORYPART TWO: THE REST OF THE STORY

CHAPTER NINE

SEEING THE EFFECTS OF THE YUGOSLAV WARS

The only sign that I had reached the Yugoslavian border were the two seemingly uninhabited houses on either side of the river. I suppose that was the border guard, but I didn’t see any living soul around.

Later in the afternoon, I reached some settlements. On the right side was the community Batina. I saw a Yugoslavian flag on the left side of the river. In hopes of finding a border guard, I headed to shore, where I landed the kayak.

The place seemed to be deserted as well. I saw a military camp and aimed for it. Outside the building there was a sign that I didn’t manage to decipher completely. The middle part was knocked down, but the word Yugoslavia was still intact.

I went in without uttering a sound. The end of a hallway led to a door that had the sign Milicija on it. My right hand was poised to knock on the door. Suddenly, the door was torn open from the inside. I was about to put my knuckles on the forehead of a wide-eyed police officer.

I quickly brought my hand down and introduced myself. The police officer led me to his captain. I walked in and stood on the carpet in front of his senior officer. I would just go over to him, extend my hand, and greet him. He did not even look in my direction, so I remained where I was, standing still. He took my passport from the police officer, then waved him out. I waited.

The Wait with the Cockroach

The captain was in his fifties, had wavy brown hair and a knobby nose. His morose face and serious disposition didn’t aid to give him a more pleasant visage. He didn’t give any of his thoughts away and nothing could be gleaned from his expression. He grabbed my passport and began to inspect it.

After an eternity, I was still standing and waiting. He finally waved me to a chair. He gave me one look. Then he resumed staring down at my red passport. I sat in the chair. He continued to stare at the passport. At some point he ran out of silence. “Johansson, Sten Christer,” were his first words, formed as a question.

“Yes.”

When we finally addressed each other, it was in German, his equally wretched as mine. “Swedish?”

“Yes.”

“With the kayak?”

It didn’t feel like I had things under control, so I had to break the ice. I saw an opportunity by making small talk about my unusual craft.

“That’s right, with a kayak! From Sweden, through Europe to the Black Sea, then Turkey and Africa,” I bubbled.

No reaction, not a look.

He repeated my data from the passport again and again.

I answered in the same fashion.

The captain continued to squint his eyes and inspect my passport, page-by-page, leaf-by-leaf. He critically reviewed each detail to detect any possible inconsistency.

I sat stiffly.

A cockroach crept along his white collar. The prehistoric animal strolled unconcernedly down his brown shirt and on to his round belly.

How would it sound if I said, “Excuse me, Captain, there’s a cockroach on your stomach.”

The idea of such bad timing brought forth a stifled laugh, quickly choked back and swallowed before anyone noticed. I sniffled the snot back and stood silent for a long moment.

The Interrogation

“Where are your papers for your kayak?” he inquired.

“Uh, I have no papers for my kayak,” I answered hesitantly.

Only then did he raise his eyes and look at me, repeating my words in a query: “No piece of paper?”

“No,” I piped back in a small voice. At that moment I dared not ask if there was a problem. I decided to keep my answers straight and simple and remain quiet as a mouse. He managed and controlled the game.

Another man with graying hair and sporting a leather vest came into the room. An air of authority enveloped him. He knew English, giving me an opportunity to turn the situation to my benefit. He warned me to go over to the Croatian side, on the right side of the Danube. Afterwards, if I decided to go back over to the Serbian or Yugoslavian side, I would run into problems. He also warned me not to paddle in the dark. Border guards got nervous easily.

He posed a question: “What do you do if a guard stops you and you cannot explain what you are doing because you do not know the language here?”

“By singing the national anthem of Sweden.” I held my right hand over my heart to demonstrate. He seemed to like the answer, judging by his smile.

For the first time, I dared to ask, “No problem?”

“No problem,” he answered.

Being Released

Four hours later, two pages of four carbon copies each filled with information about my arrival in a kayak were typed up using a 10-kg electronic typewriter. They allowed me to leave the camp, but kept three uniformed men at my heels.

After they had thoroughly inspected my watercraft, they pointed to a rusty barge: “You sleep there tonight. In the morning you will get your papers.” I was happy to oblige.

The three men who were left in charge of the barge for the night looked after me, feeding me with smoked pork, sausage, garlic, horseradish, and pepperoni. They called me Robinson. They were not Friday, but I was content.

While I was grateful that it had gone so well, the scent of problems and wars hung heavily in the air. Sitting in my kayak the next day, the feeling stayed with me as I pushed myself away from the bank.

It had been 10 years since the last time I was in the country. When I was hitchhiking around the area back then, I could feel that something was not quite right. The Serbs hated the Croats, and vice versa. Then there were the Bosnians, Macedonians, Slovenians, and Albanians, and they all thought this or that ethnic group did their best to kill everyone else.

Back then, I passed horse-drawn carts and saw bonfires in the gypsy camps at night. The only thing that unified most of the former Yugoslavia’s 22 ethnic groups was hatred against the 23rd—the gypsies.

In Kosovo I remembered the dust, poverty, armed Serbs and tanks. I was seventeen then.

Visiting Today’s Yugoslavia

Almost equally naïve, I slipped into today’s Yugoslavia, but with a greater experience with conflicts and wars from other countries. The city had been completely bombed out.

To see something on TV, to look at pictures or read an article about something that had happened was like watching from a great distance. If you were the type of person, you may even have the capacity for empathy and commitment, but usually people were apathetic. The information just passed through and the only acknowledgment was a slight shrug of one shoulder.

When I came into a small fork in the Danube, I was happy to get rid of the kilometer-wide river. Instead, I chose to follow the smaller, 20-meter-wide body of water and found many beautiful subjects to photograph—the fog, a curved tree, and birds in flight.

Another fork called me back to the mother river. As I went with the current, I saw a city on the Croatian side. It must be Vukovar, I thought, after having studied the map. I paddled closer, drawn by curiosity. Soon enough, I saw that something was not right. Except for four rebuilt towers, the town was plunged in ruins. It was more of a heap than a city. It was a disturbing sight: skeletons of houses, factories, and churches as I glided past. I was looking at the remnants of the Vukovar massacre.

The Aftermath of War

Where the hell was I when this happened? How could I have missed this? Guilt washed over me. I then realized that at the time, I was in the midst of another major conflict in another part of the world. (More on Central America another time.)

I didn’t go ashore. I could only watch and try to understand how it happened. All the trees had been cut down, all to the same height, by the grenades that had been launched from the Serbian side. They were launched at the entire city, low and mercilessly, with a wide coverage. The Serbian side had warlords lobbing their artillery over to the city across the river.

I tried to imagine what it was like here back then, the panic and fear, people trapped in their own hometown sentenced not only to fall into enemy hands, but to extinction. All of a sudden I felt the meaningless war more significantly as I listened to reports about Kosovo on the radio.

NATO threatened bombing raids, but the goals were not defined. There were also talks of Serbia. I felt no concern for my safety. The Serbs seemed to take it all in stride. On the same day that the deadline passed, they went about their day like business as usual.

Occasionally, I heard comments about the Yanks needing to clean up their act before they came here to terrorize. I saw several small boats waiting at the dock with their engines chugging, and people running to catch a ride. People in two fishing villages on the Serbian side waved at me. I did not see anyone on the Croatian side.

Mingling with the Locals

I was invited for coffee, beer, and hard liquor. These were rough men with one, two, or more teeth missing. Their language was spiced with plenty of pussy and cock whore, but beneath the unpolished surface lay kindness and hospitality.

“So, you are going to Africa. Then you may get a fat gold ring in the nose and another one in the dick!”

I got a hard slap and a squeeze on the shoulder, plus an unsolicited opinion: “Fucking idiot, fucking wrong. Kayaking in the middle of winter! But you seem to be fit, though perhaps a little on the thin side.”

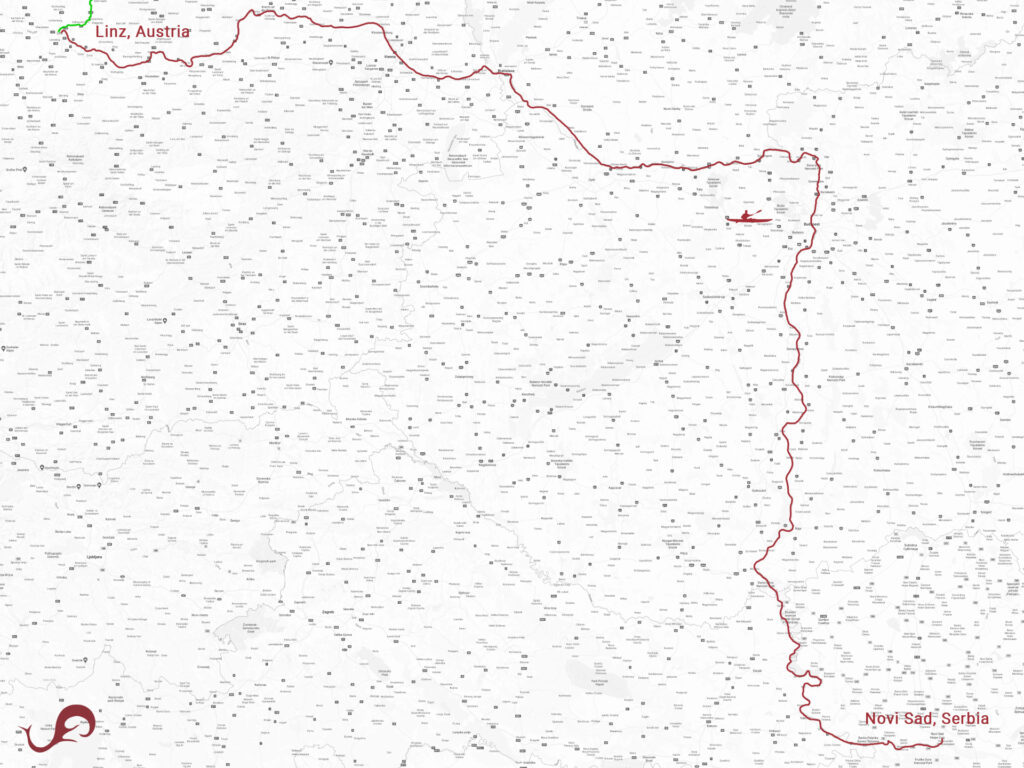

I stayed in a hotel in Novi Sad. I needed a visa to Romania, so I took the bus to the capital, Belgrade, sixty kilometers away. My Visa card didn’t work because of the outside world embargo on Yugoslavia. Through the Swedish Embassy, I was able to take out money from my bank account. I had to pay 400 Swedish crowns for the service.

After receiving the money, I left the city happy as a lark, and moved on to Belgrade. I bought cassettes of movie soundtracks by Goran Bregovich. With music in my ears, I headed to an internet cafe and, in my euphoria, wrote home ridiculous stories of my adventures. I decided not to pay a large amount of money to sleep on a bed. Instead, I invested the money in food and drinks. I crashed happily in a backyard in downtown Belgrade. That little bit of luxury was a welcome change. I enjoyed the town and its inhabitants.

Sightseeing and a Side Trip

The next morning I set out early and started taking photos. In a dark, shabby room, I had a coffee to warm up my joints. At the tables were men who were not so young, sitting in solitude and taking their breakfast in the form of beer and cigarettes. One stood out a bit more than the others: he cleared his throat of the special blend of tobacco and mucus that had accumulated in his lungs, and spat out a gob on the floor. He spoke in short sentences with a voice that vibrated like an empty oil barrel. I met his shifty eyes as he posed for my camera.

I went to the Romanian Embassy for a visa. The stamp pounded three months instead of just one. I continued with my photography.

Meanwhile, in Belgrade, I got the address of a particular Arkan, the man who was said to be behind a lot of crimes in Sweden. He was also reportedly the right hand of Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević. (Read the separate story here.)